Introduction

With retirement beckoning, it was a pleasure to be invited to reflect on my first fieldwork in 1970s Hungary and its significance for the later evolution of my career. I regret that I was still too preoccupied with my last projects at the Max Planck Institute for Anthropology to be able to write up a contribution to the volume that has already appeared (Mateoc and Ruegg 2020). The belated reminiscences that follow are excerpted from the presentation I made in Fribourg in early May 2022, when it was finally possible for some of us to gather in person.

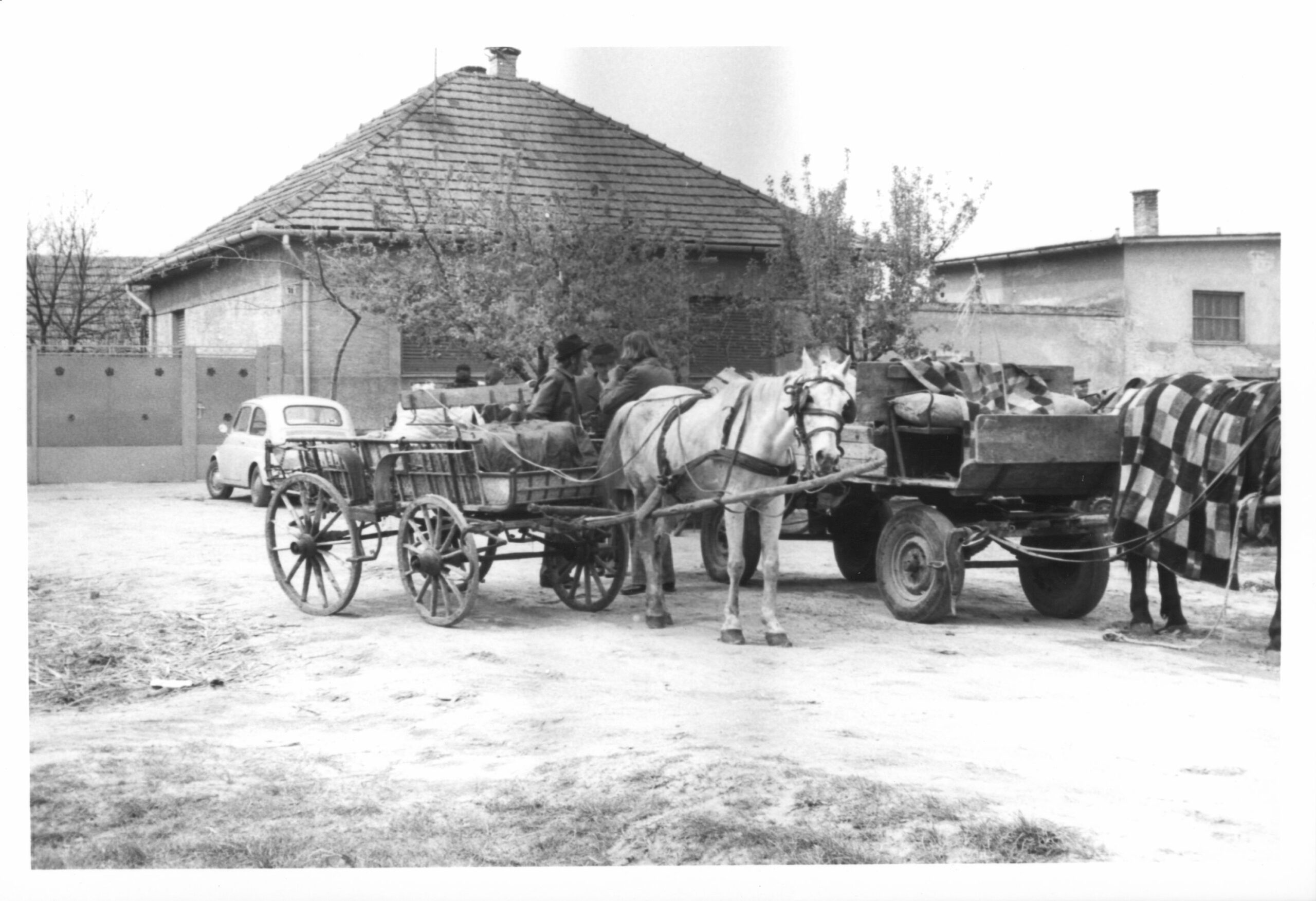

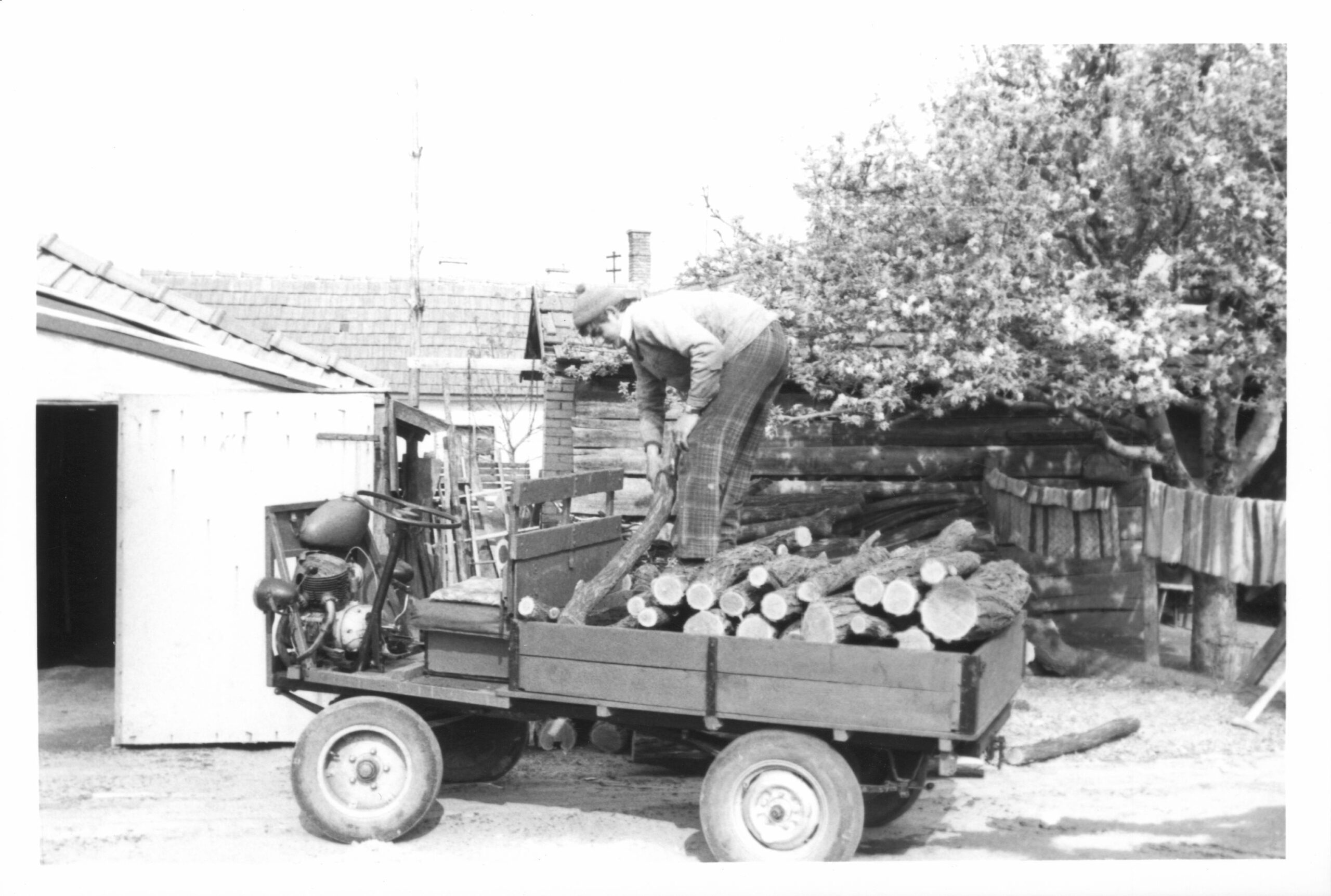

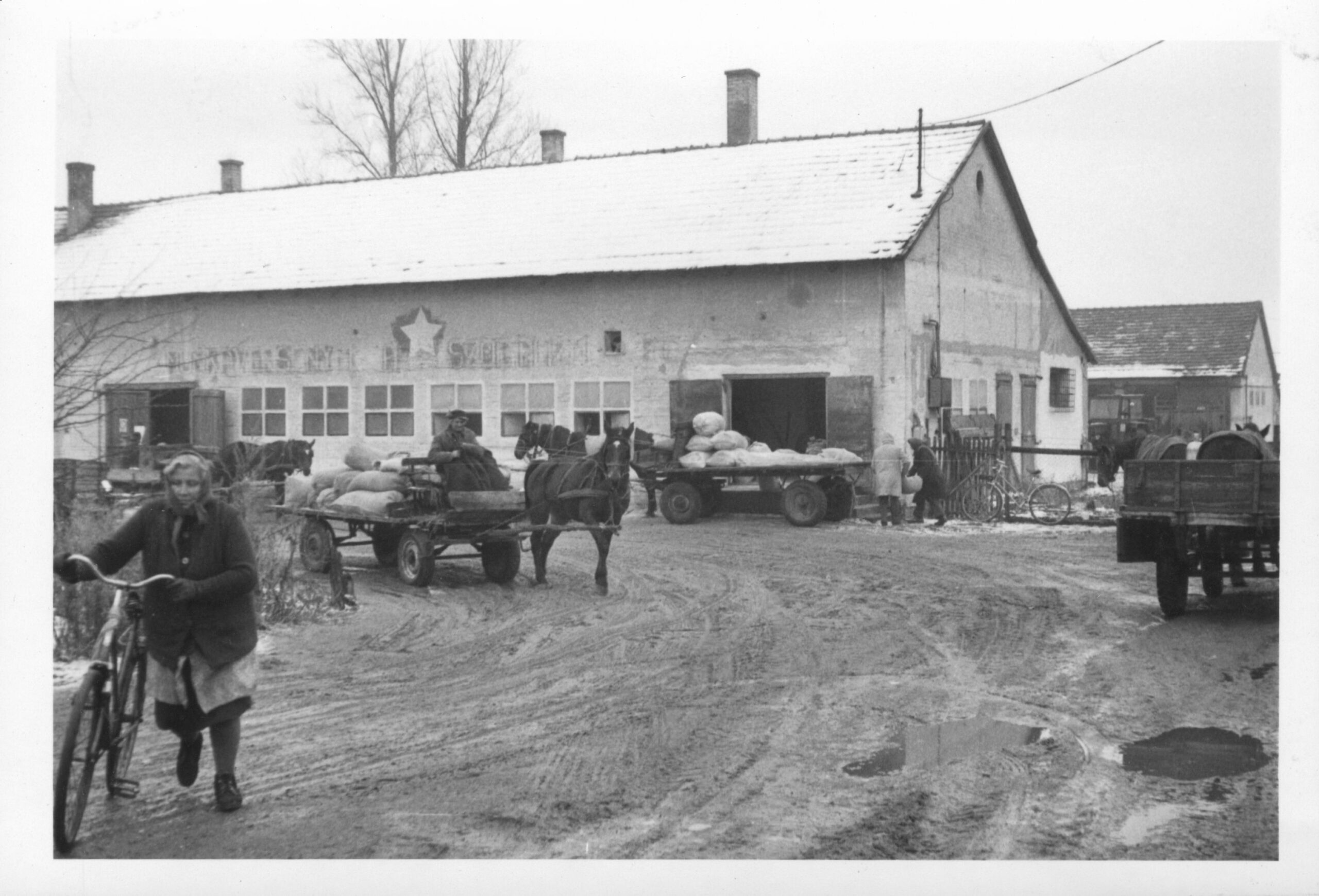

I arrived in Budapest in Autumn 1975 as a British Council cultural exchange scholar, affiliated to the Ethnographic Research Group of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. My official supervisor was the Head of the Ethnography Department, the Oceanist Tibor Bodrogi, who met me in an official Academy car when I arrived at the Keleti train station and was very surprised to discover that my Hungarian was non-existent. In practice, I was advised mainly by Mihály Sárkány, a young social anthropologist who, like me, specialized in economic anthropology, and who had been a key participant in a recent team project in a village in northern Hungary (see Bodrogi 1978). By the Spring of 1976 I was ready to scout around for a suitable place to conduct fieldwork in the second year of my scholarship. I was allowed to conduct this search free of supervision, though my advisers had from the beginning indicated that the Danube-Tisza interfluve would be the ideal location for my project. I have explained elsewhere how the choice fell on Tázlár, mid-way between the country’s major rivers, where soils are of variable quality and the summers are the driest and hottest in the country. The primary criterion was the existence of a “specialist cooperative” (szakszövetkezet) in the village. I took this institution, very different from a regular collective farm in that most villagers were still farming their traditional “peasant” holdings, to exemplify Hungary’s flexible approach to collectivization, and the relative success of the mixed socialist economy more generally (“market socialism”), following the introduction of the New Economic Mechanism in 1968.

For me as for so many others, this doctoral fieldwork was decisive for my career. I lost interest in the Western Marxist anthropology in which I had been immersed in Cambridge, which I did not find helpful in understanding the conditions I was investigating. Even before completing the PhD in 1979, I started a new project in the Polish countryside to investigate the antithesis of Hungary’s flexible market socialism. Later I worked with my wife in Turkey and in Turkic-speaking Chinese Central Asia, but the paths pursued by the villagers of Tázlár never left my mind. In the new century, this is the only field site that I continue to revisit regularly. After almost five decades, my circle of friends is inevitably diminishing. But I have maintained good relations with numerous villagers, including younger inhabitants and successive Mayors. So, when I am asked if I can submit a paper to a journal issue or some collective book project, it often transpires that I can dredge up enough relevant data from Tázlár to be able to accept the invitation.

In 1976, the chairman of the village council was not at all happy to have a young foreigner living in the village and asking his officials to supply him with all kinds of data about the local population. He thought I must be some kind of spy. I have described this elsewhere (Hann 1995, 2004). But my documents were all in the best possible order. I sometimes made mistakes, as when, right at the beginning, I signed my residency card (tartózkodási engedély) prematurely and was sent back to the capital to have a new one issued. But this episode seemed only to confirm my basic innocence. I was clumsy, barely able to understand jokes in Hungarian. I was young (and looked even younger), a student of ethnography (néprajz), rather than a sociologist; and certainly not a political scientist. I had no car and relied on the local buses like everyone else. It helped that I rented a room on the main street from an elderly widow, a devout Roman Catholic who provided the perfect foil to my associations with cooperative managers and other officials. Only the council chairman and the parents of the coolest unmarried girl in the village saw me as a threat; and even they mellowed eventually.

I have never been tempted to look up my files at the Ministry of the Interior in Budapest, though I have been told that some documentation is archived there. I am afraid it might be too embarrassing. I am embarrassed about inadvertently causing a friend made through the sports club I trained with to lose his employment at this Ministry (my friend had volunteered to develop my photographs at his workplace: this was another example of my naivety). To the best of my knowledge I did not bring such misfortune on anyone else, either in the village or in the capital.

Political Tensions

For all my naïve blundering in the field and my neglect of anthropological theory, one element remained constant in those formative years: political predilections. Most of those who signed up for research in socialist Eastern Europe had leftist orientations. For obvious reasons, such sympathies were hard to sustain in the Romanian case; or, if they lingered, it was sympathy for a completely different version of socialism than that which they encountered in the field.

My case in Hungary was more complex. What I found in the field resembled what Gerald Creed (1998) and Martha Lampland (1995) theorized more effectively for Bulgaria and Hungary respectively. In my reading, the latter ends up more critical than Creed of the rampant commoditization of the last socialist decades. I too was critical. I concluded my monograph with the suggestion that the extreme decentralization of the “specialist cooperative” in the general framework of market socialism was generating a return to older forms of inequality, as well as pathologies of overwork and materialist consumerism. A convergence with more standard forms of collective farming was therefore desirable. Of course, this was the opposite of what actually happened, since those larger socialist institutions were privatized in the 1990s. More significantly, it was also the opposite of what the great majority of villagers themselves wanted. This tension persisted throughout my first fieldwork; in different forms, it is still there when I visit the village today, since my own sympathies differ from theirs.

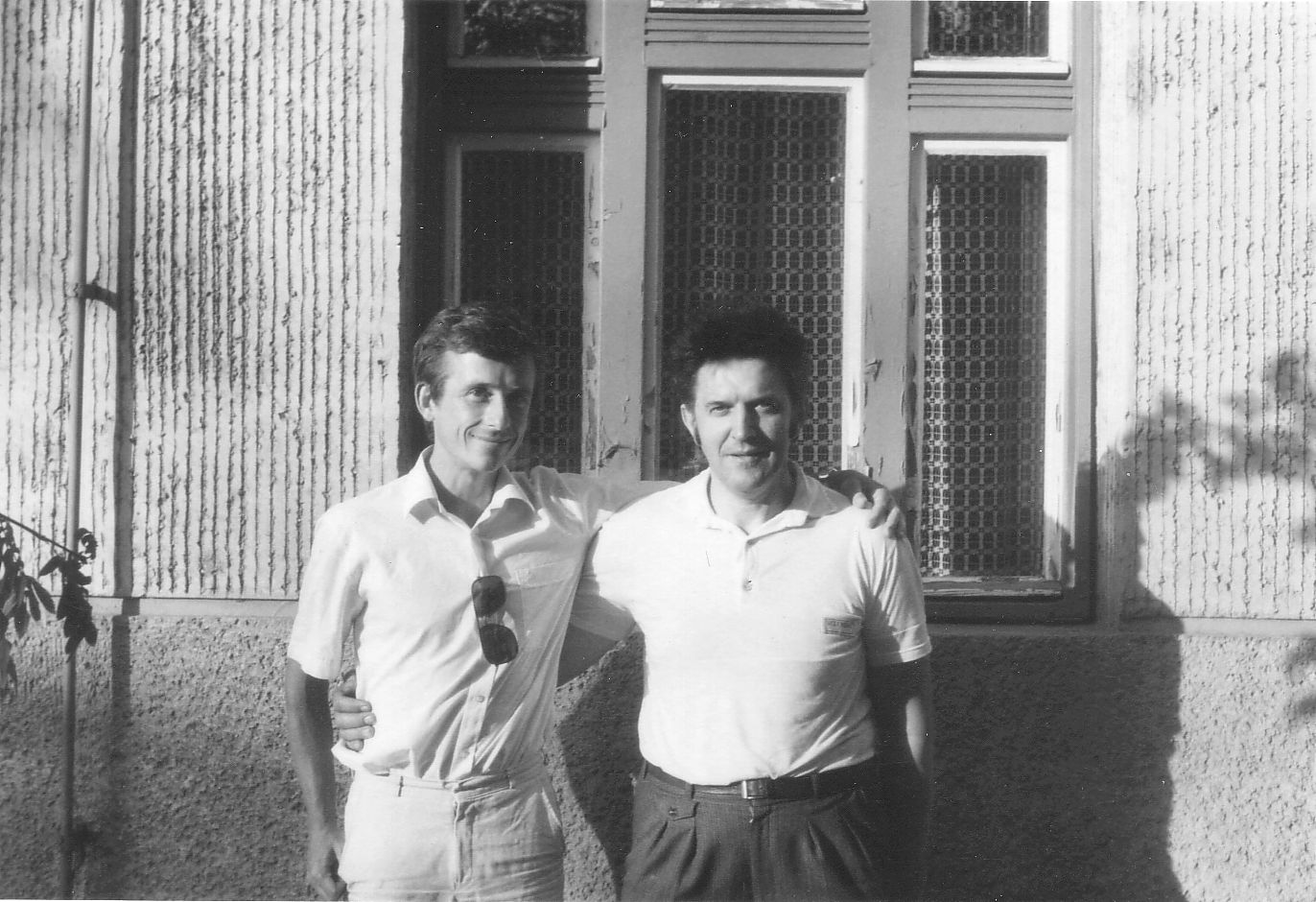

My closest associate throughout the research was the agronomist responsible for maximizing production in the household sector (háztáji agronómus). Sándor Dúl lived in a nearby town but was constantly under way in his Trabant along the sandy roads of Tázlár. I learned an awful lot from hanging out with him, and from conversations with other, more technocratic colleagues, who had taken over the leadership of the specialist cooperative shortly before my field research began. Most of these men must have been Party members, but this was not something we discussed. Villagers, by contrast, were overwhelmingly anti-communist. They expressed such views privately, but by the mid-1970s some were not afraid to lambast the cooperative leadership at general assemblies, when district-level comrades were in attendance. The majority seemed to view these moments of protest (which came mostly from older villagers) as theatre; they accepted that ordinary members could not hope to change ideological directions that were determined at the county capital and ultimately in Budapest (if not Moscow). In my book, in addition to documenting the lack of democracy in the cooperative and in the “elected” council, I included material revealing a moribund culture house and suggested that the chairman of the council was personally corrupt. I am not sure this was ethical and would probably be more cautious in such circumstances today. In any case I was vindicated because, shortly after my fieldwork, a local entrepreneur trapped this communist leader, who lost his post and received a suspended prison sentence after being found guilty of accepting bribes in return for approving farmstead electrification.

In spite of all the imperfections of Kádár’s socialist system, I never lost my sympathy for it. You can attribute this to my own positionality and political formation in a western capitalist world in which the USA was already the principal rogue state (above all in Vietnam) and Britain was never far behind. After the “change of system” (rendszerváltás) I took pleasure in observing even inveterate anti-communists coming around, at least in private, to recognize the positive aspects of socialism, above all the material progress made both privately and publicly in its last decades, compared to what occurred after 1990. In the one-party system of today, socialism is denounced by the government. The present Mayor is a member of Fidesz. A respected teacher at the village primary school, he ran a successful campaign in 2014 (Hann and Kürti 2015). The defeated incumbent of 20 years had no party affiliation. His family were a bulwark of the middle peasantry and he himself was a very dynamic entrepreneur in the vineyard sector. The Mayor is aware that I do not share his political convictions, but he is not as suspicious of my activities as the council chairman in the 1970s (he has no reason to be).

I took part in a rather moving event in the culture house in 2017, when I was asked by the author of a history of the community to introduce the volume to a large audience at the culture house. János Horváth was a village teacher in Tázlár for most of his life (see Hann, forthcoming 2022). Deputy Head of the primary school at the time of my research, he was known to be a Party member. I had no business in the school and we never became friends, though we encountered each other occasionally on the football field and at weddings, where he played keyboards in the “teachers’ orchestra”. When the council chairman was removed following the entrapment I mentioned above, János took over, in addition to his responsibilities for the school, culture house and library. He was one of the first to resign his Party membership in 1989. János did not contest the first democratic elections, preferring to concentrate on his main job in the school. Following retirement, he did run for Mayor, but he was defeated by the independent candidate mentioned above (who was endorsed by the local branch of the Smallholders’ Party). János was greatly respected as a teacher and cultural animator, but when it came to political office, the scion of an established middle peasant family was considered preferable to an ex-communist “turncoat” (köpönyegforgató).

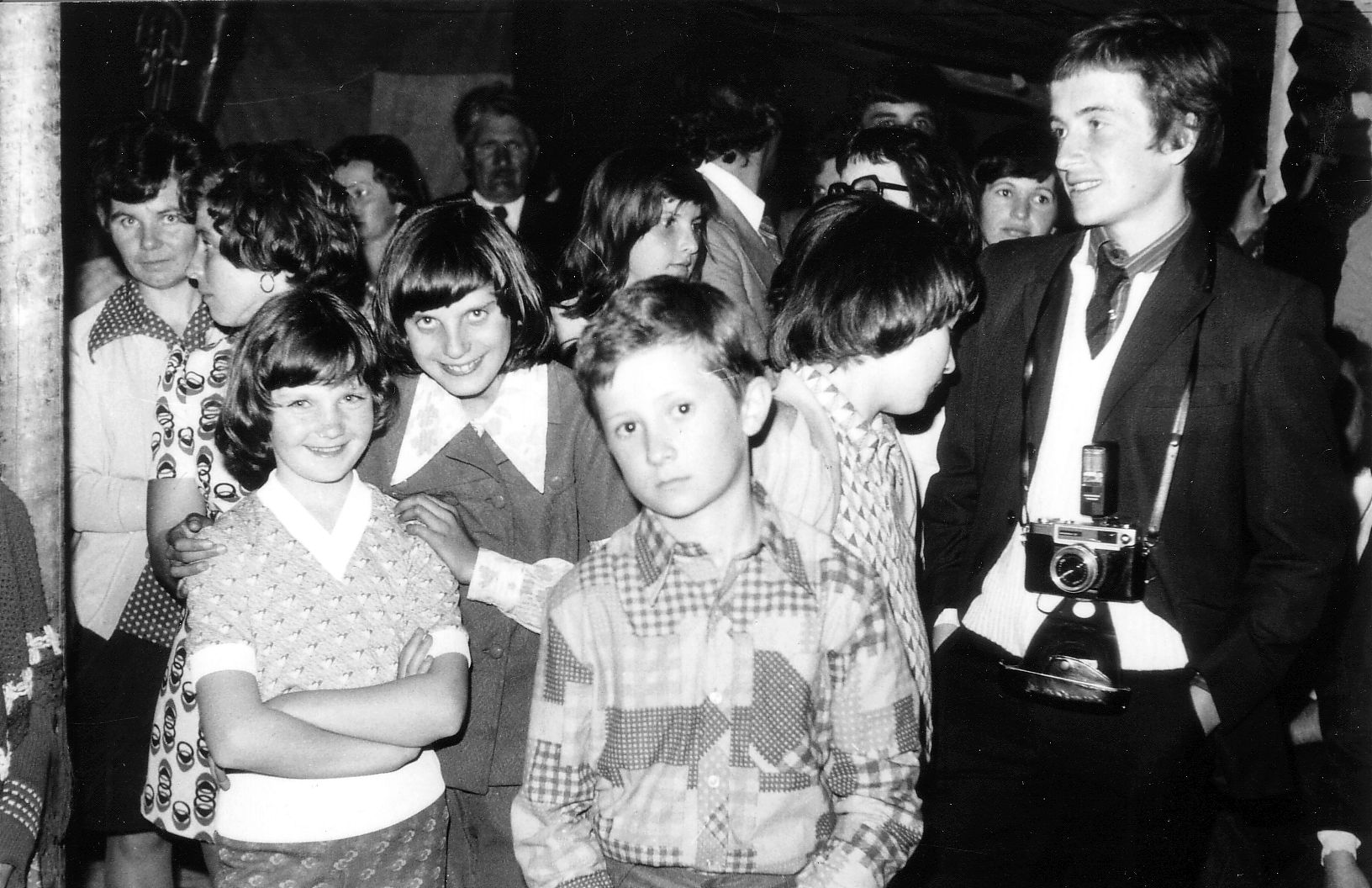

In the years after 1990, I visited János and his family regularly. He continued to organize clubs and events at the culture house. His monograph of Tázlár’s modern history was impeccably researched. Prior to its publication, the new Fidesz Mayor (who had been appointed to his post at the school by János) proposed conferring the community’s highest honour on its outstanding public servant. However, this was opposed by two elected members who could not bear the thought of an ex-communist being made an honorary citizen. When they would not modify their intransigence, the Fidesz mayor invented a new title that he could bestow without needing the support of other elected councillors. This was duly conferred on János immediately before my own contribution. I couldn’t help thinking that some members of the audience on that summer evening might have had similar feelings towards me as they felt towards János. Whatever the political positions and the values we had been associated with in the past and indeed the present, we had in our very different ways demonstrated loyalty to this community over several decades, and this was appreciated. Many of the photographs on display that evening in the culture house were black and white pictures taken by me during my original fieldwork.

Conclusion: blundering and plundering

Encouraged by Raluca Mateoc, I have reflected on my own path as a fieldworker, in particular on the consequences of the year I lived in Tázlár in 1976-77, which involved the loss of earlier theoretical enthusiasms, but the retention of political preferences. Katherine Verdery writes (in her contribution to Mateoc and Ruegg 2020) about the advantages of going back again and again to the same place. I would like to second this by referring back to the distinction drawn by Tamás Hofer (2005) in his well-known contribution to Current Anthropology in 1968, in which he contrasted the long-term commitments of native ethnographers, immersed in their culture since childhood, to the “slash and burn” approach of the comparativist from abroad who carries out one intensive burst of fieldwork and then moves on. I did move on to other countries. But I also returned again and again to Tázlár, perhaps making fewer blunders as the years went by, perhaps still plundering in the sense that I always took notes and continued to publish articles and chapters. Obviously Tázlár can never be my home. But I visit regularly, usually accompanied by my own family. I have a godson there; I am in touch with one of his brothers, who has emigrated to Britain; I maintain correspondence with members of the Tázlár diaspora elsewhere in Hungary, and with several families in the village, including that of János Horváth, who passed away just over a year ago. In short, this Hungarian village has become a very important element in my life and that of my own family.